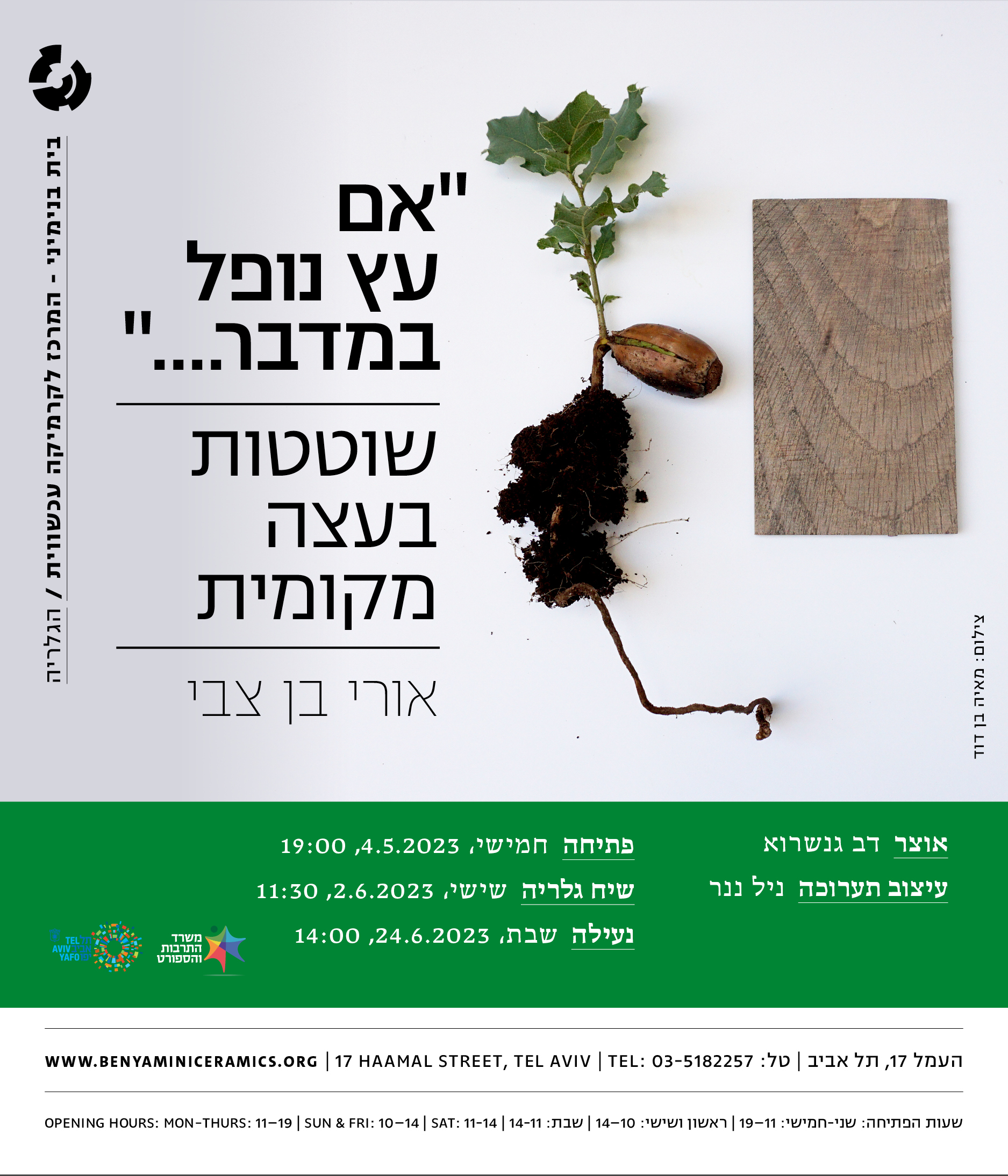

“If a tree falls in the desert…”- Roaming the local cambium / Ori Ben Zvi

Curator: Dov Ganchrow

Opening: Thursday, 4/5/23, 19:00

Gallery talk at Benyamini center: Friday, 2/6/23, 11:30

Closing: Saturday, 24/6/23, 14:00

Strolling alone through the spacious exhibition venue of the 2012 Budapest Design Week, I paused to observe a work resting on a slightly elevated platform at the conflux of two adjoining halls. It was a wooden stump stool, or rather it was a stump form, constructed of many smaller pieces of wood assembled in Butcher Block manner. It was meticulously smoothed, polished, and lacquered, its sensual surface curvature enveloping and wrapping the individual wood slats into one complete entity.

I remember thinking to myself “now that’s a design work that wouldn’t be made back home”.

That evening at the exhibit’s opening, the curator introduced me to the “other Israeli” attending the show – Ori Ben-Zvi. To my astonishment, the stump work I had pondered over that same morning was his – its origin not at the hands of a Dutch designer or Brazilian design studio.

There are possibly two ‘take-aways’ from this incident; firstly, it might be useful to, at times, read labels next to works at exhibitions. Secondly, it’s worth giving thought to what constitutes local? What is perceived as local? And why?

Much of Ori’s professional life has been dedicated to working with wood, it is his material of choice, and through it he has pursued the greater topics of ‘ecology’ and of ‘locality’.

Understanding the character of a material will inevitably lead to better design when working with that material. In the case of wood, understanding grain type density, material weaknesses to humidity or parasites, odor, growth structure related to a plank’s former location in a tree trunk, scarcity etc., allows for well-minded applications. Ori acknowledges that after focusing on wood as a material for many years, there came a moment of enlightenment when his viewing angle of wood grew from simply ‘present to future’, into ‘past to present to future’; An extended understanding of a tree that becomes wood that becomes furniture.

Through his past experience working on furnishings based on reclaimed wood, Ori was accustomed to scouting material, of tracking down potential. Whether perceived as an act of hunting or of gathering, the process undoubtedly taught him much about locality, both prime geographic (urban) sources, or regarding the local customs of what and when things are discarded.

Ori’s current exploration (he prefers the term “roam”, expressing a slightly less dogmatic undertaking) of tree-wood relations is also of highly local character. There are several expressions of local throughout; the first is engaging with the mapping of tree species through the terms of indigenous as opposed to invasive or introduced, here local must be tied to chronological time. The existence of a tree species growing where in the past it had not, could be attributed to climate change, politics, commerce, technology, immigration, and policy, to name a few.

Geography is another tree-wood exploration necessary, the Oak forests at the base of Mount. Hermon, the more solitary Acacia growing in a Negev riverbed, KKL-JNF forests being groomed for fire threats, the ‘new generation’ sawmill in Emek Hefer, or the Hebrew University’s Faculty of Agriculture, Food and Environment in Rehovot. All places he roamed.

Local turned out to also include a network of locals on the ground; tree-felling contractors, lumber entrepreneurs, tree-hugging (tracking) activists, policy makers, academia botanists, carpenters, and designers, each with their own perspectives and insights.

His journey has brought Ori to understand that what captivates him most is the tree-wood’s state of being when in limbo. A limbo between two identities, two purposes, two worlds. Solid tree trunks huddling motionless on the earth in a lumberyard not far from a powerful serrated steel saw blade. The trunk, although technically a dead tree, has not yet completed its journey to becoming lumber, from where its onward journey to product is pretty much assured. Its appearance at this point, more a tree than that of a raw material, its past and its future in sight, it is in a transit state – not actually a place.

Sprouting from this gap in transformed identity are a couple of works in the exhibition: “Segments” consisting of pieces of partially planed tree-wood volumes, exemplifying many of the species found locally. Not unlike a forest they stand together, but they are individuals, baring their characteristic colors, annual ring density, and at times bark.

The chunky cubic trunk segment in “Looking at the Tree”, shifts its line of sight back in time, using light to project an “shadow” image of its former self boasting a full leafy foliage.

“Sliced” has taken a step forward; a step through the sawmill, but without leaving the lumber yard. Typically, a log, after being planked, is set aside to dry slowly over a period of time. Wedges are inserted between planks to let air vent moisture. Ori plays on this image/technique by politely asking us to stand up from the trunk on which we were resting, then reseating us as soon as it has exited the other side of the saw as a series of consecutive planks. We will now refer to it as a bench, it has been shifted from improvised seating to designed.

While much of what Ori gathered over the past couple of years was information, there remained the question of whether information was what would be displayed to gallery visitors? What would be the balance of information and of design? How objective and how subjective? It was the pursuit of information that helped map out locality, but it was Ori’s actions or restraint that produced the displayed outcomes. The pairing of lichens and wood in “Not the Tree by Itself”, is in essence a botanic description of an eco-relationship between organisms. The specific wood type, now a material block contrasting the natural forms of the specific fungi composite, has become a podium, a museological means of display, elevating the lichen for visitors. Only through the realization of the work as a collection of lichen-wood pairs, do the botanic relationships become apparent, transforming visitors into observers (or forcing them to read the label…).

All this brings us full-circle back to the question of perceived ‘local’ as raised earlier in the Budapest Design Week anecdote; Did Ori’s stump stool represent a subject matter that is nearly nonexistent in the Levant for lack of contemporary lumber forests? Or was the mislocation due to the skillful workmanship not often seen in a culture that rewards things done, not the qualitative manner in which they are done? Even the subtle sculpting of the stump, a form that did not force itself on the wood, seemed out of place when most of the locally assembled wood to be found is on construction sites, where 4” nails reign.

The Hebrew language, with its limited – or minimalist vocabulary, uses the same word “etz” to describe both a tree as well as the material derived from it – wood, while Arabic, similarly to English, has at least two different dedicated words. It seems that the single dual-meaning Hebrew term “etz” has been around a while, appearing in the Bible 329 times and used there roughly equally to describe either a tree or wood while conceptually making the two inseparable. “Etz” exposes the human interest vested in a tree, while at the same time forever reminding us of the material’s origin.

Local will have to remain in perpetual critical evaluation, while the local version of the classic proverb might now read:

“If a tree falls in the desert and no one is around to hear it, does it make a sound?”

אם עץ נופל במדבר_שוטטות בעצה מקומית _אורי בן צבי_צילום שי בן אפרים

אם עץ נופל במדבר_שוטטות בעצה מקומית _אורי בן צבי_צילום שי בן אפרים

אם עץ נופל במדבר_שוטטות בעצה מקומית _אורי בן צבי_צילום שי בן אפרים

אם עץ נופל במדבר_שוטטות בעצה מקומית _אורי בן צבי_צילום שי בן אפרים

אם עץ נופל במדבר_שוטטות בעצה מקומית _אורי בן צבי_צילום שי בן אפרים

אם עץ נופל במדבר_שוטטות בעצה מקומית _אורי בן צבי_צילום שי בן אפרים

אם עץ נופל במדבר_שוטטות בעצה מקומית _אורי בן צבי_צילום אורי בן צבי

אם עץ נופל במדבר_שוטטות בעצה מקומית _אורי בן צבי_צילום אורי בן צבי

אם עץ נופל במדבר_שוטטות בעצה מקומית _אורי בן צבי_צילום אליה לוי יונגר

אם עץ נופל במדבר_שוטטות בעצה מקומית _אורי בן צבי_צילום אליה לוי יונגר

אם עץ נופל במדבר_שוטטות בעצה מקומית _אורי בן צבי_צילום שי בן אפרים

אם עץ נופל במדבר_שוטטות בעצה מקומית _אורי בן צבי_צילום שי בן אפרים

אם עץ נופל במדבר_שוטטות בעצה מקומית _אורי בן צבי_צילום שי בן אפרים

אם עץ נופל במדבר_שוטטות בעצה מקומית _אורי בן צבי_צילום שי בן אפרים

אם עץ נופל במדבר_שוטטות בעצה מקומית _אורי בן צבי_צילום שי בן אפרים

אם עץ נופל במדבר_שוטטות בעצה מקומית _אורי בן צבי_צילום שי בן אפרים

אם עץ נופל במדבר_שוטטות בעצה מקומית _אורי בן צבי_צילום שי בן אפרים

אם עץ נופל במדבר_שוטטות בעצה מקומית _אורי בן צבי_צילום שי בן אפרים

אם עץ נופל במדבר_שוטטות בעצה מקומית _אורי בן צבי_צילום שי בן אפרים

אם עץ נופל במדבר_שוטטות בעצה מקומית _אורי בן צבי_צילום שי בן אפרים

אם עץ נופל במדבר_שוטטות בעצה מקומית _אורי בן צבי_צילום שי בן אפרים

אם עץ נופל במדבר_שוטטות בעצה מקומית _אורי בן צבי_צילום שי בן אפרים

אם עץ נופל במדבר_שוטטות בעצה מקומית _אורי בן צבי_צילום שי בן אפרים

אם עץ נופל במדבר_שוטטות בעצה מקומית _אורי בן צבי_צילום שי בן אפרים

אם עץ נופל במדבר_שוטטות בעצה מקומית _אורי בן צבי_צילום שי בן אפרים

אם עץ נופל במדבר_שוטטות בעצה מקומית _אורי בן צבי_צילום שי בן אפרים

אם עץ נופל במדבר_שוטטות בעצה מקומית _אורי בן צבי_צילום שי בן אפרים

אם עץ נופל במדבר_שוטטות בעצה מקומית _אורי בן צבי_צילום שי בן אפרים

אם עץ נופל במדבר_שוטטות בעצה מקומית _אורי בן צבי_צילום שי בן אפרים

אם עץ נופל במדבר_שוטטות בעצה מקומית _אורי בן צבי_צילום שי בן אפרים

אם עץ נופל במדבר_שוטטות בעצה מקומית _אורי בן צבי_צילום שי בן אפרים

אם עץ נופל במדבר_שוטטות בעצה מקומית _אורי בן צבי_צילום שי בן אפרים

אם עץ נופל במדבר_שוטטות בעצה מקומית _אורי בן צבי_צילום שי בן אפרים

אם עץ נופל במדבר_שוטטות בעצה מקומית _אורי בן צבי_צילום שי בן אפרים

אם עץ נופל במדבר_שוטטות בעצה מקומית _אורי בן צבי_צילום שי בן אפרים

אם עץ נופל במדבר_שוטטות בעצה מקומית _אורי בן צבי_צילום שי בן אפרים

אם עץ נופל במדבר_שוטטות בעצה מקומית _אורי בן צבי_צילום שי בן אפרים

אם עץ נופל במדבר_שוטטות בעצה מקומית _אורי בן צבי_צילום שי בן אפרים

אם עץ נופל במדבר_שוטטות בעצה מקומית _אורי בן צבי_צילום שי בן אפרים

אם עץ נופל במדבר_שוטטות בעצה מקומית _אורי בן צבי_צילום שי בן אפרים

Invitation

Invitation