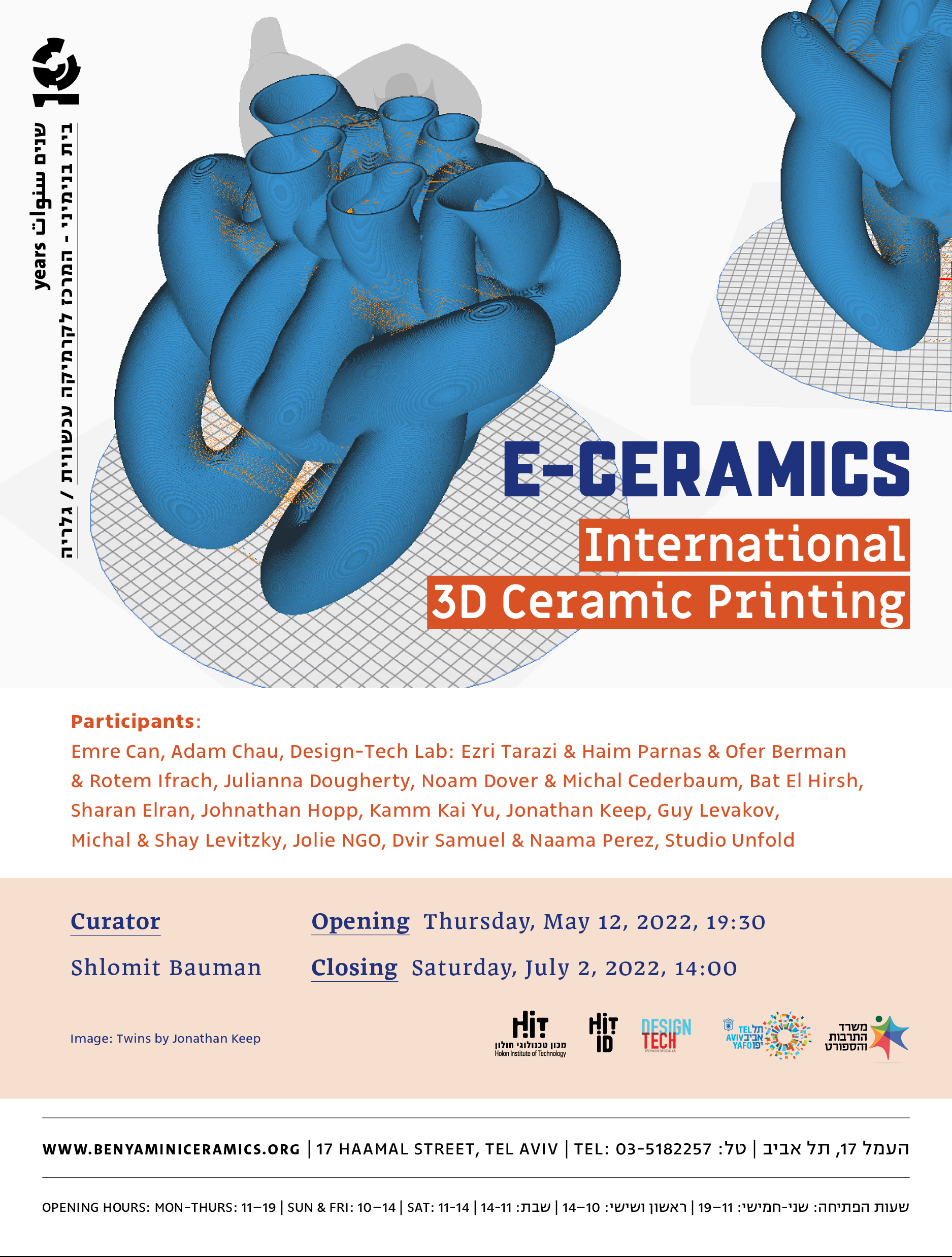

E-Ceramics / group exhibition

International 3D ceramic printing

Opening: Thursday, 12/05/22 at 19:30

Gallery Talk: Friday, 17/06/22 at 11:30 at the Benyamini Center

Online artist’s talk: Wednesday, 29/06/22 at 19:30- For registration

Closing: Saturday, 02/07/22 at 14:00

Curator: Shlomit Bauman

Emre Can, Adam Chau, Design Tech – Ezri Tarazi & Haim Parnas & Ofer Berman & Rotem Ifrach, Julianna Dougherty, Noam Dover & Michal Cederbaum, Bat El Hirsh, Sharan Elran, Johnathan Hopp, Kamm Kai Yu, Jonathan Keep, Guy Levakov, Michal & Shay Levitzky, Jolie NGO, Dvir Samuel & Naama Perez, Studio Unfold

The transition to using digital design tools has permeated art, design, and craft for several decades and its affect is well presented. In the past few years digital tools that in the beginning were used to design and produce prototypes, have now become production tools for making art and design objects. Digital production methods create a new language of objects that do not depend on molds and release angles. These tools do not require large production series and it is possible to change their scale and easily print works of different sizes by adjusting the digital file.

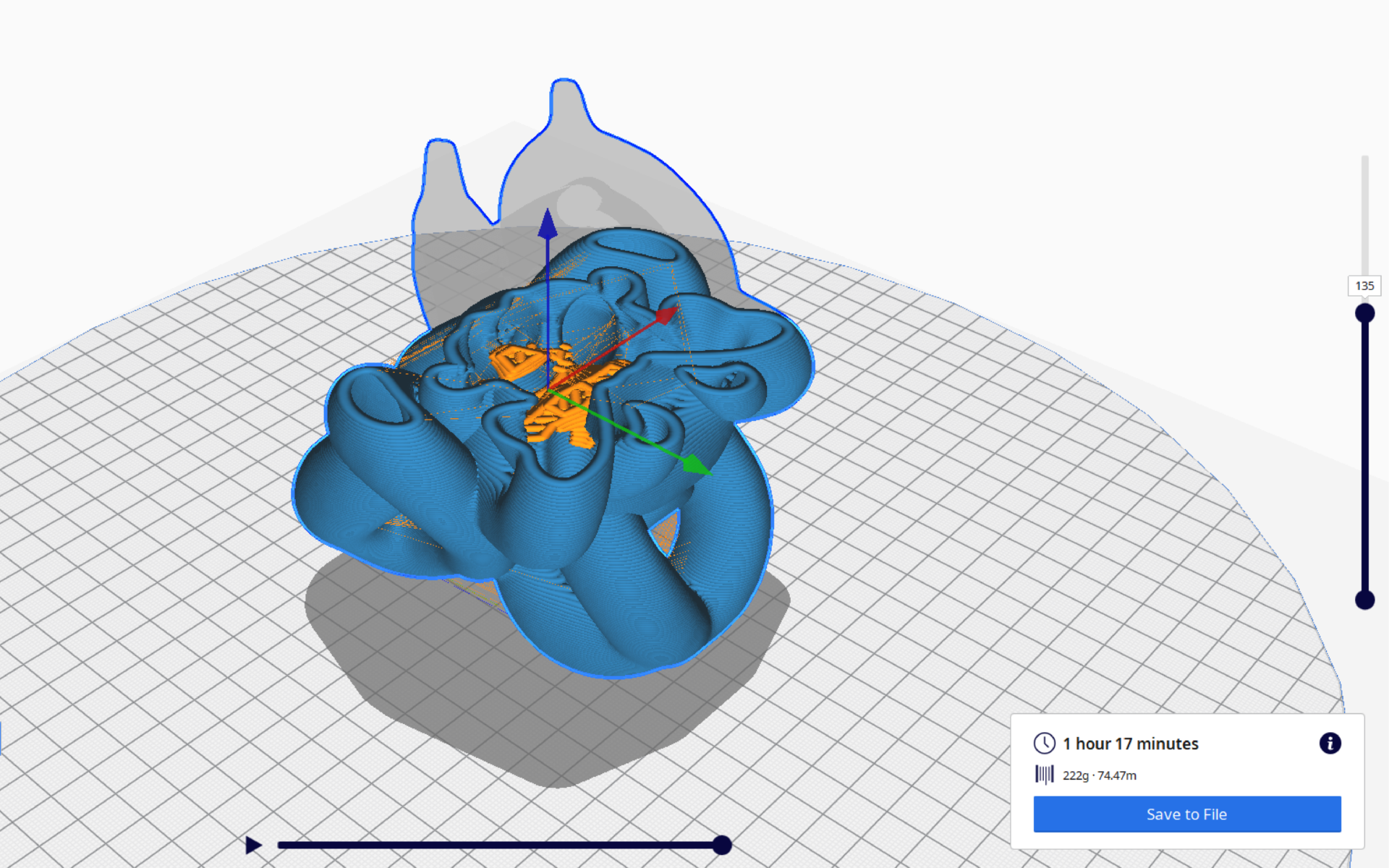

In ceramics this technology removes the need to make a model and creates a new dialog between the digital world and clay that has the characteristics of an ancient tradition. In the first years of the ceramic 3D printer, designers and craftsmen that were pioneers in the field, examined the capabilities and limitations and the expression in design and art. The 3D ceramic printer is now becoming more common as a tool for expression in academies and makers around the world, producing new bodies of works.

At the outset, the idea was to present an exhibition of Israeli and International designers and makers, leaders in the field of 3D ceramic printing. However, the Covid pandemic shuffled the cards and digital media became even more prevalent in our lives. Shipping valuable works of art and design became an even bigger hurdle with the rising costs of insurance and the value of the works themselves as well as the unreliability of shipping. All these factors were the trigger for a change of concept: Designers and artists would send files of their work to the gallery which would then be printed using local resources and these would be exhibited in the gallery. This is a cheap sustainable solution saving resources wasted in transportation of international exhibitions. In addition, this approach would allow participants to exchange ideas based on ‘open source’, to question fundamentals and raise new questions about the relationship between planning and producing in 3D ceramic printing. The process caused the 3D ceramic printer to become the “super-translator”: would printing the same file on different printer give the same result as accepted when digitally printing polymer products? Or would the outcome be affected by the type of printer, the character of the producer, the raw materials, the glaze, the kiln, etc?

The exhibition E-Ceramics created a challenge to decipher the digital file and to create an artwork that can present itself as such. Each of the persons in Israel who printed the files was confronted with international communication and all that it entails including bridging language, cultural and technological differences.

The works in the exhibition illustrate the potential of the language of forms in 3D ceramic printing. If in the first years of the technology we were witness to testing the limits of the form in this field and the freedom from the limitations of handmade and ceramic industry, today – we can say that this language has become part of a broad cultural statement that includes new technologies as well as relevant questions about personal and gender identity, local versus global, functional versus abstract worlds, sustainable versus processes that are wasteful of resources and raw materials.

Invitation

Invitation

E-Ceramics_Space_Photo Shay Ben Efraim

E-Ceramics_Space_Photo Shay Ben Efraim

E-Ceramics_Space_Photo Shay Ben Efraim

E-Ceramics_Space_Photo Shay Ben Efraim

E-Ceramics_Space_Photo Shay Ben Efraim

E-Ceramics_Space_Photo Shay Ben Efraim

E-Ceramics_Space_Photo Shay Ben Efraim

E-Ceramics_Space_Photo Shay Ben Efraim

E-Ceramics_Space_Photo Shay Ben Efraim

E-Ceramics_Space_Photo Shay Ben Efraim

E-Ceramics_Space_Photo Shay Ben Efraim

E-Ceramics_Space_Photo Shay Ben Efraim

E-Ceramics_Space_Photo Shay Ben Efraim

E-Ceramics_Space_Photo Shay Ben Efraim

E-Ceramics_Studio Unfold_Atlas of Lost Finds_Photo Shay Ben Efraim

E-Ceramics_Studio Unfold_Atlas of Lost Finds_Photo Shay Ben Efraim

E-Ceramics_Studio Unfold_Atlas of Lost Finds_Photo Shay Ben Efraim

E-Ceramics_Studio Unfold_Atlas of Lost Finds_Photo Shay Ben Efraim

E-Ceramics_Sharan Elran (AoLF)_Photo Shay Ben Efraim

E-Ceramics_Sharan Elran (AoLF)_Photo Shay Ben Efraim

E-Ceramics_Noam Dover and Michal Cederbaum (AoLF)_Photo Shay Ben Efraim

E-Ceramics_Noam Dover and Michal Cederbaum (AoLF)_Photo Shay Ben Efraim

E-Ceramics_Noam Dover and Michal Cederbaum_Photo Shay Ben Efraim

E-Ceramics_Noam Dover and Michal Cederbaum_Photo Shay Ben Efraim

E-Ceramics_Michal and Shay Levitzky_Photo Shay Ben Efraim

E-Ceramics_Michal and Shay Levitzky_Photo Shay Ben Efraim

E-Ceramics_Kamm Kai Yu_Photo Shay Ben Efraim

E-Ceramics_Kamm Kai Yu_Photo Shay Ben Efraim

E-Ceramics_Julianna Dougherty_Photo Shay Ben Efraim

E-Ceramics_Julianna Dougherty_Photo Shay Ben Efraim

E-Ceramics_Jolie NGO_Photo Shay Ben Efraim

E-Ceramics_Jolie NGO_Photo Shay Ben Efraim

E-Ceramics_Johnathan Hopp_Photo Shay Ben Efraim

E-Ceramics_Johnathan Hopp_Photo Shay Ben Efraim

E-Ceramics_Guy Levakov_Photo Shay Ben Efraim

E-Ceramics_Guy Levakov_Photo Shay Ben Efraim

E-Ceramics_Emre Can_Photo Shay Ben Efraim

E-Ceramics_Emre Can_Photo Shay Ben Efraim

E-Ceramics_Dvir Samuel and Naama Perez_Photo Shay Ben Efraim

E-Ceramics_Dvir Samuel and Naama Perez_Photo Shay Ben Efraim

E-Ceramics_Jonathan Keep_Twins_Photo Shay Ben Efraim

E-Ceramics_Jonathan Keep_Twins_Photo Shay Ben Efraim

E-Ceramics_Jonathan Keep_Twins_Photo Shay Ben Efraim

E-Ceramics_Jonathan Keep_Twins_Photo Shay Ben Efraim

E-Ceramics_Bat El Hirsh_Photo Shay Ben Efraim

E-Ceramics_Bat El Hirsh_Photo Shay Ben Efraim

E-Ceramics_Bat El Hirsh_Photo Shay Ben Efraim

E-Ceramics_Bat El Hirsh_Photo Shay Ben Efraim

E-Ceramics_Bat El Hirsh_Photo Shay Ben Efraim

E-Ceramics_Bat El Hirsh_Photo Shay Ben Efraim

E-Ceramics_Design Tech_Photo Shay Ben Efraim

E-Ceramics_Design Tech_Photo Shay Ben Efraim

E-Ceramics_Design Tech_Photo Shay Ben Efraim

E-Ceramics_Design Tech_Photo Shay Ben Efraim

E-Ceramics_Design Tech_Photo Shay Ben Efraim

E-Ceramics_Design Tech_Photo Shay Ben Efraim

E-Ceramics, Adam Chau. Photo: Shay Ben Efraim

E-Ceramics, Adam Chau. Photo: Shay Ben Efraim

E-Ceramics_Experiments_Photo Shay Ben Efraim

E-Ceramics_Experiments_Photo Shay Ben Efraim

E-Ceramics_Experiments_Photo Shay Ben Efraim

E-Ceramics_Experiments_Photo Shay Ben Efraim

E-Ceramics_Experiments_Photo Shay Ben Efraim

E-Ceramics_Experiments_Photo Shay Ben Efraim

E-Ceramics_Experiments_Photo Shay Ben Efraim

E-Ceramics_Experiments_Photo Shay Ben Efraim