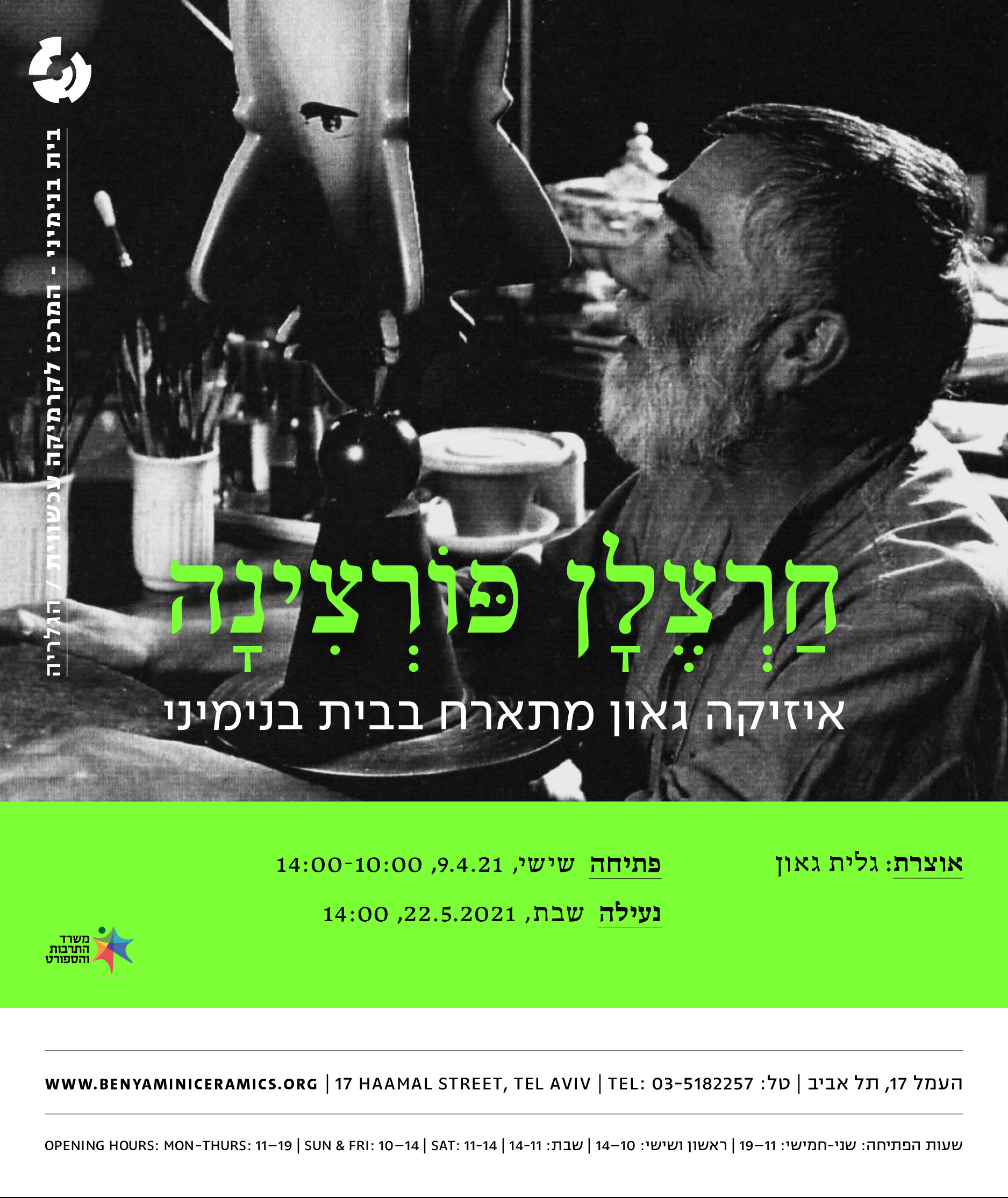

Harzelan Porchina / Izika Gaon, a guest at the Benyamini Center

Curator: Galit Gaon

Opening: Friday, 9.4.2021, 10:00-14:00

An online Gallery Talk: Wednesday 5.5.21, 18:00, For registration An online Gallery Talk about the exhibition Harzelan Porchina / Izika Gaon

Closing: Saturday, 5.6.2021, 14:00

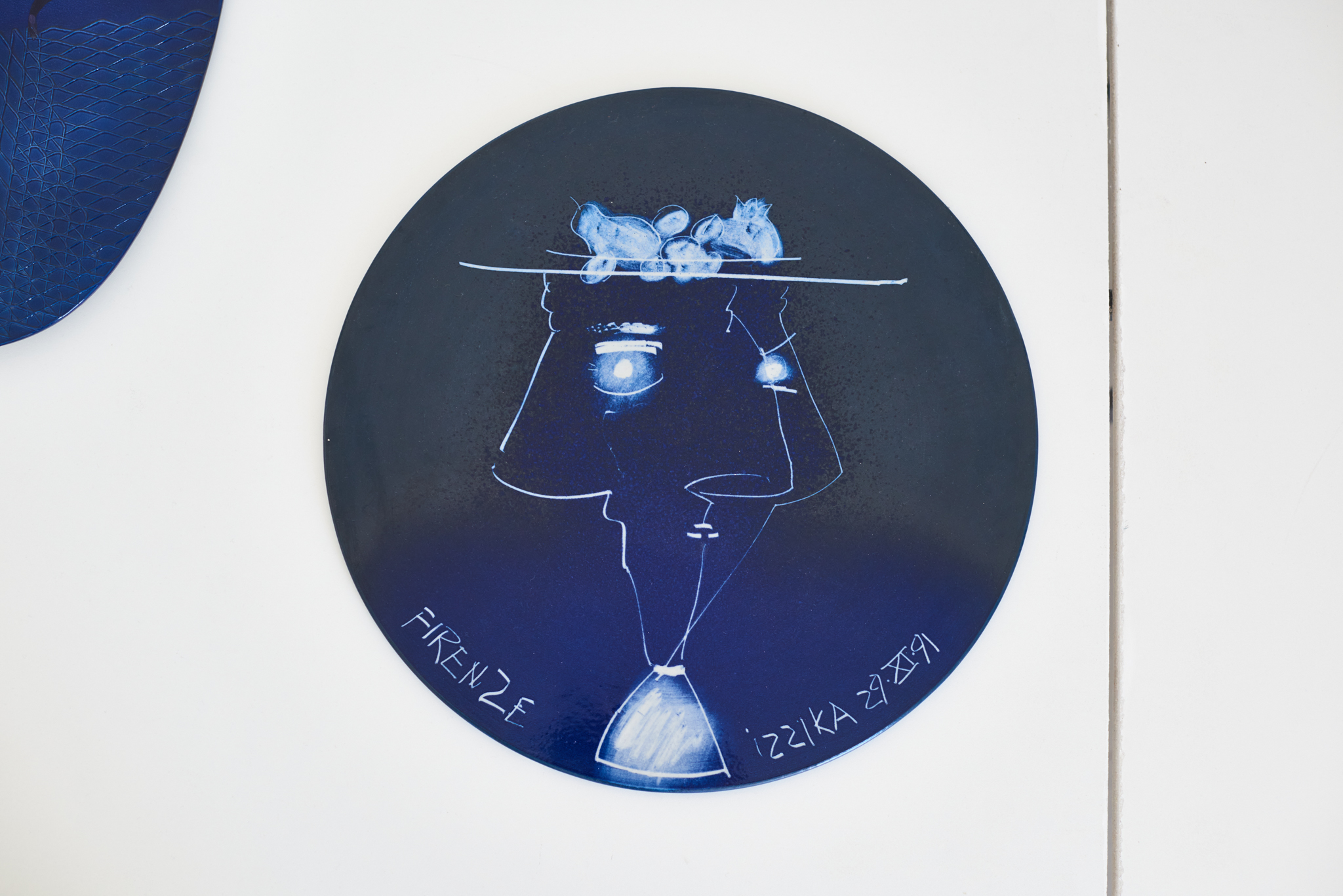

Izika, a guest of the Benyamini Center, is the best definition of the exhibition at the Benyamini Ceramics Center. Even though we parted 24 years ago, Izika is present in our lives daily. Artist, maker, curator, and a people’s person, host, traveler, dreamer, happy emigrant. In the later years of his life, he found great interest in making porcelain, stuck in the workshop in Florence where he embarked on a journey of new colors and forms as a canvas for free expression of subjects that interested him since he was a young student at Bezalel – the image of a head, a self-portrait between a dream and the fear of death.

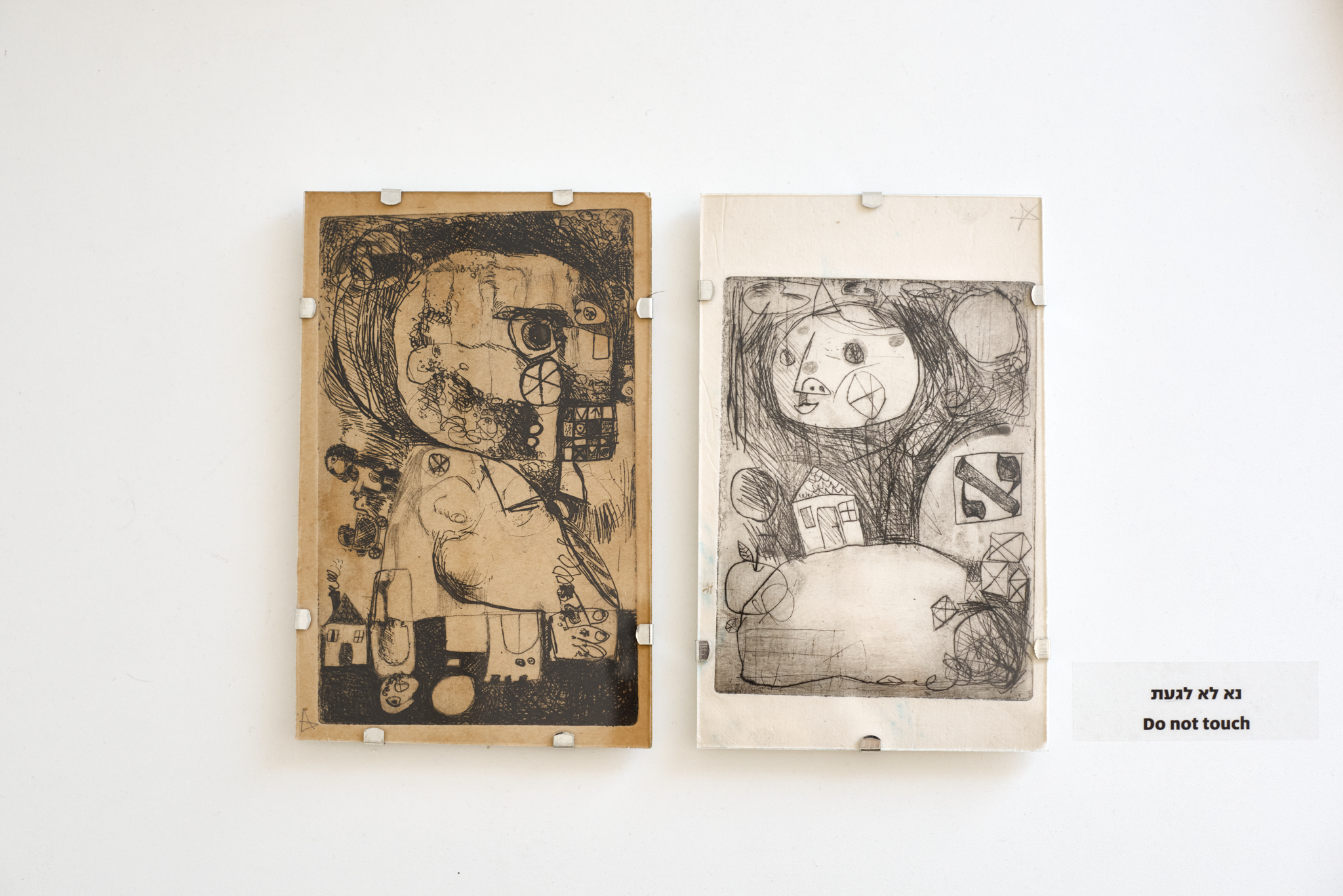

In preparation for the exhibition, I returned to his black notebooks – his well-known sketch books, looking for signs of his journey, traces of the head, questions of identity and migration, emigration and belonging. Artists, makers, and designers carry them from place to place, like a portable device of strength, notebooks that formally carry words, ideas, visions, and reflections next to thoughts and fears, personal reminders, and ideas for the future. The notebooks of Izika beside the sketches are parts of a diary, a calendar with business cards, parts of maps and remarks on the side. I follow him through the small signs that he left, paging backwards and forwards, I meet the artist, the curator, the designer and even my father. All together they comprise a stormy picture of passion and interest, love, and creativity. The artist, pushed to the sidelines while working in the museum, looking for a way out as he overruns the protocols of meetings with drawings in black lines. The curator, trying to order his raging thoughts, makes lists and lists of thoughts and dates, and the designer sketching pedestals and posters, thoughts of the display experience and the audience. And my father, who stuck our letters into one of his notebooks when he travelled far away.

But behind all of them, is a man that did not totally find himself and his point of view being an immigrant, a frightening dream that never left him. Izika came to Israel as a boy after the Second World War, where he grew up on a Moshav with his parents who arrived in Israel not out of choice, and who expressed their dissatisfaction that they could not stay in Yugoslavia and were forced to live in an abandoned chicken run in the village. At the first opportunity he left home and went to study far away at the Technical Airforce School in Haifa and from there he progressed to become an airplane mechanic in the air force. The choice he made to go to that school could be traced to a meaningful event in his childhood during the war when a pilot from the allied forces landed close to the partisans in the forests of Yugoslavia: in his pocket he had a treasure for children during the war – white bread. The pilot was the first soldier that Izika saw that symbolized the victory over the Nazis, the freedom, and the dream to return home. Towards the end of the war the Jews of Yugoslavia were gathered in a camp next to Italian soldiers. The soldiers were enchanted by the fair curly haired inquisitive little boy, and they gave him chocolate, teaching him words in Italian and calling him “bambino”. He would say “the Italians saved me in the beginning”. Perhaps that is the reason for the large collection of Italian design as opposed to others, in the Israel Museum Collection of architecture and design which he managed for 30 years. Rightly so and not because of the chocolate. In the eighties and nineties, the Italians were leaders in the field with new ideas and breakthroughs in design, but they also symbolized for Izika the road to free creativity and making. There he found his way in the last decade of his life creating in porcelain and glass, heads dreaming, frightened, filled with color and materiality, painted, and drawn with surprising softness.

The pages of the notebooks can be divided into several categories. Those of the artist that recall memories translated quickly, those of the frustrated curator picking at the edge of the notebook with words of anger “how can one speak of art without artists”, next to many angry pages covered subsequently in colored collages. Those of the department director with lists of exhibitions, dates, donors, and meetings and next to them chaotic pages with outbursts of emotion of a curator – maker that cannot control the words and thoughts on one page. And four pages. The edge of the notebook of ’96. “Beware of August” he wrote to himself. Noting to himself it appears, the end that is drawing closer.

Paging through, I understood that he knew we would read them. Pages stapled or glued together so we could not read them, pages written in all different directions, where circles and arrows direct the reader in the reading sequence which is not necessarily the sequence of writing. There are notebooks that are illustrated with happiness and excitement that is evident on each page, such as the notebook from the trip to Japan or the notebook from the end of the sixties, a trip to Mexico with short letters, excited descriptions before travelling to the Macho Picchu in an open jeep. In all of them, it is clear the great passion to belong to a place, a time, a language.

I miss him, the way in which he managed to look at reality with fresh eyes – as a boy that redesigns his lost childhood through exhibitions, friends, long dinners loaded with words and food, an abundance of good and joy. Wandering, it appears, served Izika well when each time he left to discover a new part of the world. Preparing the journey, dedicated to spontaneous movement that usually led to good ideas, and new friends who helped blur the loneliness a bit.

As a maker – artist he looked to encounter reality with its full power. Staying in one house appeared to him to be too little when beyond Ben Gurion there is a whole world of new possibilities free of nationality and identity. It was important for him to be clear – legible – simple – at eye level. As a man who was in constant motion, on an endless journey where he benefited from being a wanderer, emigrant, not belonging. He saw reality clearly and accurately because of this unique viewpoint. Settling down for him symbolized petrification, being stuck and conservative, which he tried to avoid until his death. Taking a long look, the order of his calendar, the many meetings, business cards, protected him from his wandering spirit to move freely according to the issue, to look for new connections, the moments where new thoughts arise and so remain a wanderer of ideas, an emigrant of thoughts and a happy man, sensitive and unusually generous.

Izika, a guest at the Benyamini Center, presents the works he loved to make in the last decade at the Mangani porcelain workshop in Florence. Colorful, fragile, and pushing the limits of the material, the firing, and the impossible combinations. In all of them appear the drawn heads, the sculpted heads, reflecting, bearing, and hiding, carrying colorful Italian dreams of freedom and liberation and the sorrow of the encroaching departure, much too soon.

Harzelan Porchina, the name I found in the sketchbook of ’96 was handwritten in Hebrew with vowels and expresses the term porcelain china in Serbo-Croation.

harzelan square_invitation

harzelan square_invitation

איזיקה גאון_צלם דור קדמי

איזיקה גאון_צלם דור קדמי

איזיקה גאון_צלם דור קדמי

איזיקה גאון_צלם דור קדמי

איזיקה גאון_צלם דור קדמי

איזיקה גאון_צלם דור קדמי

איזיקה גאון_צלם דור קדמי

איזיקה גאון_צלם דור קדמי

איזיקה גאון_צלם דור קדמי

איזיקה גאון_צלם דור קדמי

איזיקה גאון_צלם דור קדמי

איזיקה גאון_צלם דור קדמי

איזיקה גאון_צלם דור קדמי

איזיקה גאון_צלם דור קדמי

איזיקה גאון_צלם דור קדמי

איזיקה גאון_צלם דור קדמי

איזיקה גאון_צלם דור קדמי

איזיקה גאון_צלם דור קדמי

איזיקה גאון_צלם דור קדמי

איזיקה גאון_צלם דור קדמי

איזיקה גאון_צלם דור קדמי

איזיקה גאון_צלם דור קדמי

איזיקה גאון_צלם דור קדמי

איזיקה גאון_צלם דור קדמי