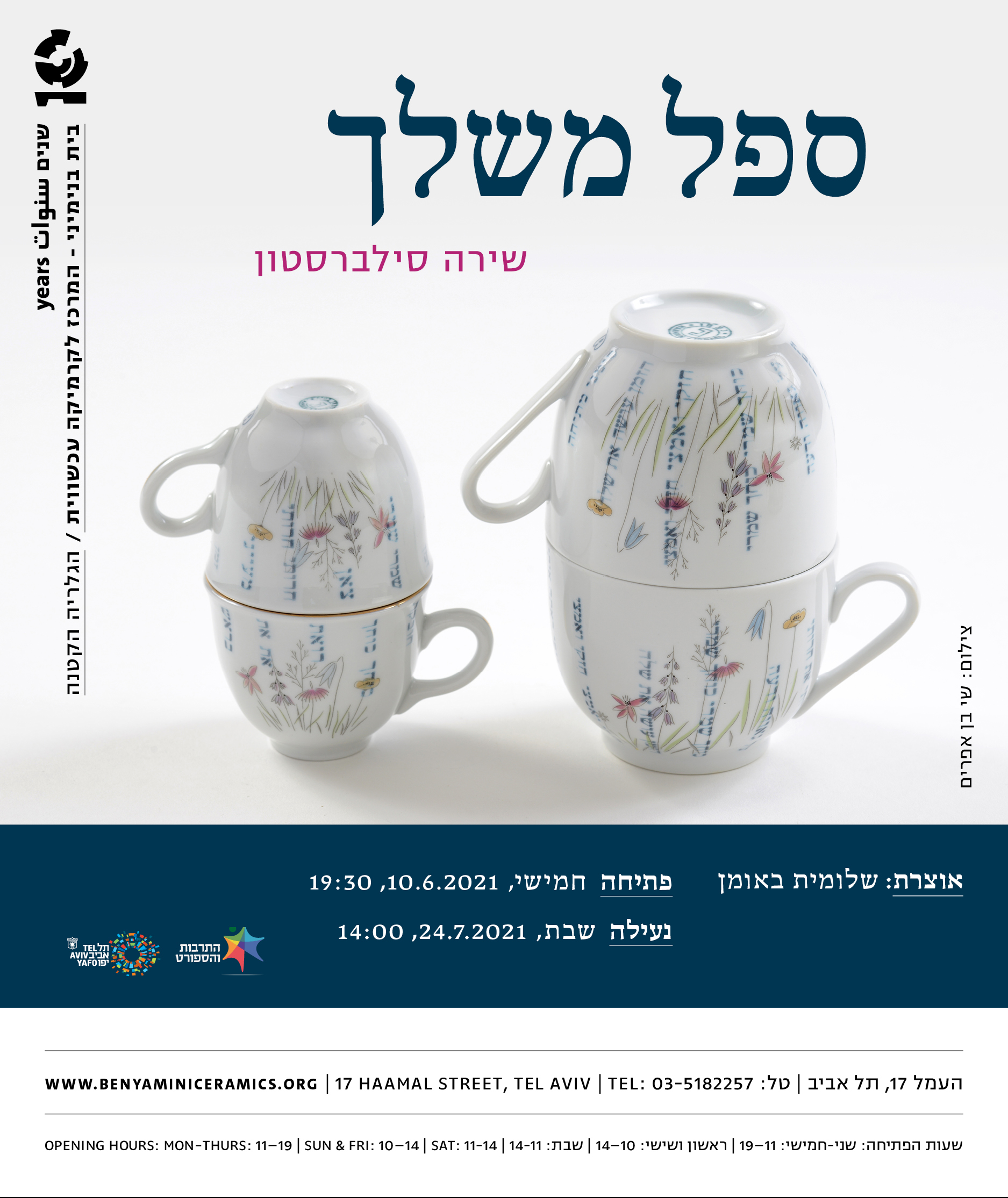

A cup of her own / Shira Silverston

Shira Silverston

Curator: Shlomit Bauman

Opening: Thursday, 10.6.2021, 19:30

An online gallery talk: Wednesday 7.7.21, 19:30– Registration

Closing: Saturday, 24.7.2021, 14:00

Is a cup a house? Is a cup a place? The choice made by Shira Silverston to use cups as a ground for this exhibition begins with the personal, intimate, and sensual connection we have with cups. We touch them with our hands, lips, and tongue, hug them, hold them to our bodies – loving acts. Cups are part of us, so much so that we take them for granted. Everyone has a favorite cup, drinking habits, and preferences: the kind of drink dictates the material, transparency or opacity, size, texture, type of handle, etc. Cups are also a sign of culture, and the choice made by Silverston to use cups by Naaman, connects the individual to the social and makes a personal statement about an industrial object which is part of local history.

Industrial ceramic houseware made by “Naaman”, which was an operational factory in the Krayot in Israel until it closed in 1996, is an integral part of Israeli Identity (today Naaman Porcelain is produced in Turkey and China). In recent years, collecting industrial Israeli ceramics made between the fifties and nineties of the previous century, has become extremely popular. Silverston became interested in this trend and herself became a collector of Naaman cups.

Silverston’s investigation of the concept “local” through Naaman cups raises many questions: What is the essence of this “local”? Is it deceptive? What lies between collective and personal? How can we decipher the language of cups?

In the Naaman factory they made houseware from porcelain, considered the elite of the ceramic materials, but this is the most distant from local – Israeli; there is no local porcelain and so it was imported from Europe (especially Germany and France). At the beginning of the 20th Century porcelain production was well ingrained in Europe, who were exposed to its beauty through trade with China which began in the 17th Century. The production of porcelain in Israel began with the desire to preserve European culture in a young and developing Israel. After failing to manufacture a porcelain body locally using imported kaolin with local raw materials, the production at Naaman was based on imported porcelain with original designs as well as copies of designs popular in Germany, Poland, and other countries.

By using Naaman porcelain cups from different periods, Silverston questions the nature of “local” which was based on a group of immigrants looking for their cultural language by preserving what was familiar to them by importing materials and forms from Europe.

Silverston puts aside the modernist, white, undecorated cup. As a member of a family of several generation of immigrants from Europe, South America, and the USA, she chooses a very particular kind of Naaman cup which she connects to through the yearning for another culture instilled in her as a child: copies of European ceramic toys, cups with floral decorations and gold trim, curved and embellished, giving a deceptive feeling of home. From another angle – the choice of the decorated, pretty, “made-up” hinting at European Art Nouveau, and turns the cups into a metaphor of the old-fashioned view of “femininity” and undermining it obsessively.

The first move made by Silverston is to challenge the connection between local industrial production and “local” as a separate value. The second move is the connection Silverston makes between the personal and the cultural and creates another layer with the flow of associative words she places on the decorated and pretty cups. The words do not remove the function of the cup – but add another layer of meaning, as Silverston explains: “I want people to drink from these cups and swallow the words as well when they use them. “

The flow of words selected by Silverston come from the personal and the associative: reversed use of gender, quotes from favorite poems, words that clarify identity: femininity and body, time and culture, industry and nature.

The words are printed on the cups in dark blue as part of a long tradition in ceramic making. They move from cup to cup, between cup and saucer, big and small, connected and separate, connected to the cups and disconnected, blending in and defiantly placed. On one hand they do not make the cups dysfunctional but revive them and restore their functionality– but on the other hand, they take over. The delicate porcelain cups barely contain the flood of words that have settled on them. The words take over from the underside to the lip, crossing their surface and even changing the decorations (also imported from Europe).

Silverston embarked on a journey in search of “A cup of her own”, relentless, searching history and personal biography, a search that challenges convention and particularly examines: What is the cultural and local meaning of each cup? What is the discourse between cups that are part of a group? Is a cup a piece of history? Is a cup a canvas? Is a cup a woman? Or is a cup a poem?

Invitation

Invitation

ספל משלך_שירה סילברסטון_צלם דור קדמי

ספל משלך_שירה סילברסטון_צלם דור קדמי

ספל משלך_שירה סילברסטון_צלם דור קדמי

ספל משלך_שירה סילברסטון_צלם דור קדמי

ספל משלך_שירה סילברסטון_צלם דור קדמי

ספל משלך_שירה סילברסטון_צלם דור קדמי

ספל משלך_שירה סילברסטון_צלם דור קדמי

ספל משלך_שירה סילברסטון_צלם דור קדמי

ספל משלך_שירה סילברסטון_צלם דור קדמי

ספל משלך_שירה סילברסטון_צלם דור קדמי

ספל משלך_שירה סילברסטון_צלם דור קדמי

ספל משלך_שירה סילברסטון_צלם דור קדמי

ספל משלך_שירה סילברסטון_צלם דור קדמי

ספל משלך_שירה סילברסטון_צלם דור קדמי

ספל משלך_שירה סילברסטון_צלם דור קדמי

ספל משלך_שירה סילברסטון_צלם דור קדמי

ספל משלך_שירה סילברסטון_צלם דור קדמי

ספל משלך_שירה סילברסטון_צלם דור קדמי

ספל משלך_שירה סילברסטון_צלם דור קדמי

ספל משלך_שירה סילברסטון_צלם דור קדמי

ספל משלך_שירה סילברסטון_צלם דור קדמי

ספל משלך_שירה סילברסטון_צלם דור קדמי

ספל משלך_שירה סילברסטון_צלם דור קדמי

ספל משלך_שירה סילברסטון_צלם דור קדמי

ספל משלך_שירה סילברסטון_צלם דור קדמי

ספל משלך_שירה סילברסטון_צלם דור קדמי